How I Do - Powershell Organization

EDIT: 2019-02-05: As I’m moving this over to my new host, I’d like to call out that this is still very relevant to the way I organize Powershell modules today. I’ve moved up from contributing to modules weekly to almost daily!

This is a how-I-do post about organizing Powershell code. As the title suggests, this is simply how I do things at this particular moment.

Is it just me or are there actually more uses for custom Powershell modules in the day to day operations? From pure laziness (not wanting to open up SQL Server Management Studio just to grab a status/field/connection string/

The light at the end of that tunnel requiring a bug fix in a large Powershell script –with zero unit tests (of course) — may finally be within sight.

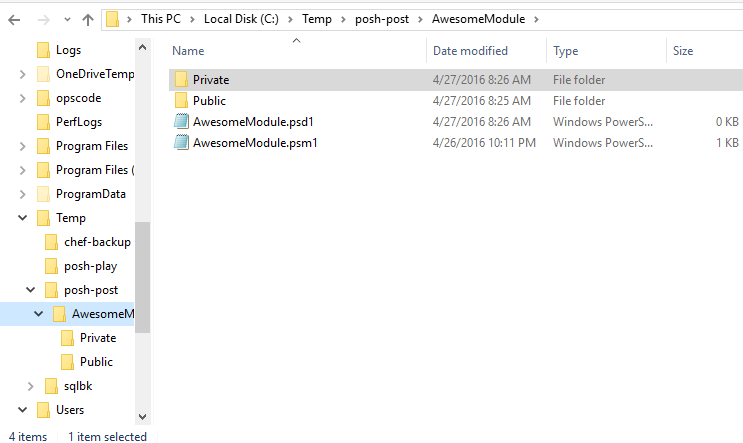

My modules all start out with this structure:

- AwesomeModule

- AwesomeModule.psm1

- AwesomeModule.psd1

- README.md

- Private

- PrivateFunction1.ps1

- PrivateFunction1.Tests.ps1

- Public

- ExportedFunction.ps1

- ExportedFunction.Tests.ps1

Now this looks pretty standard to me. The module lives in its own folder, named the same as the module. There’s a Powershell data file (.psd1) with the metadata about the module. The key take-away here is that each function is isolated in a separate file, with a corresponding test broken up into two categories (Private & Public). Private functions do not get exported from the Module, they generally contain less formal documentation and more developer comments. The private functions are not usually properly named (verb-noun) but more of a proper descriptive name. Public functions on the other hand are exact opposite. They all have external-facing documentation, formatted so that Get-Help AwesomeModule looks as it should.

EDIT: 2019-05-05: The only difference I would recommend to this layout is moving it all into a top-level src folder in order to store the module source code today and not cloud it up with extra repo artifacts, like build scripts and documentation.

I find it super easy to add new functionality or change existing functionality when each unit of code is isolated and tested individually. My module file (AwesomeModule.psm1) doesn’t actually contain any functions. In my mind, this file should be used to import other necessary modules, setup the context for the execution, and export the public functions. Many times, these files are less than 50 lines. The trick to tying all of this together is to dot source all of the functions in the private & public folders so that they are available in the context.

# if debugging, set moduleRoot to current directory

if ($MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path) {

$moduleRoot = Split-Path -Path $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path

}else {

$moduleRoot = $PWD.Path

}

# Load up the dependent functions

"$moduleRoot\Public\*.ps1", "$moduleRoot\Private\*.ps1" |

Resolve-Path |

Where-Object { -not ($_.ProviderPath.ToLower().Contains('.tests.')) } |

ForEach-Object { . $_.ProviderPath }

# Export the public functions

Export-ModuleMember ExportedFunction

By using $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path, I can source the functions located in my module directory, no matter what directory I’m actually in. This is important to understand because $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path is $null when executing it in a user session. That’s why I’m checking for that value, and when not found, setting it to $PWD.Path will allow me to quickly source my functions for a debugging session (all of my functions in the private & public folders are made available in my current session). The dot source happens in the ForEach-Object { . $_.ProviderPath } which if you squint really hard, the . (period) can be seen.

Pester already searches recursively thru the directory it’s pointed at, so there’s nothing additional needed to test. Open up a Powershell session in the AwesomeModule directory and run Invoke-Pester and all of your Pester tests are executed. This also works nicely with Pester’s InModuleScope functionality.

As usual, thanks for reading! Any questions and/or comments are welcome (and appreciated). Would love to hear more from you about how you organize your Powershell code.